Making Decisions and Analyzing the Facts

By Brice Palmer

[NOTE: REGISTER for the next workshop with Brice scheduled May 21 at 7:30 PM ET;

We all have them. Dark and stormy nights before Team meetings. We burn the midnight oil combing through the records looking for FAPE denying critters camouflaged by vague, symbolic, and sometimes meaningless language hiding in 8 point type.

It can get ugly.

We stress out. We know the meeting is going to be another IEPcalypse. The school’s side of the table will be loaded with more people than the IDEA calls for. The school district’s lawyer will be there – and – sometimes claims to be a “member” of the Team because the school invited them to attend. The facilitator or compliance coordinator will be there. And, they will all be talking over one another. Precious time wasted by a cacophonic chorus.

Sometimes we get stretched to the breaking point. We must complain. So we complain. And we complain again. And we complain again. We begin to ask ourselves whether anyone ever listens.

In a movie called Sweet Liberty, Alan Alda played a history professor whose book was picked up by a movie studio. The movie folks moved to the professor’s home town to film the story. Of course the screen writers and movie producer immediately began tweaking the story, the period costumes, and so forth – The professor was furious. So we complain. And we complain again. And we complain again. We begin to ask ourselves whether anyone ever listens.

The professor collared the director and said something to the extent the contract said he, the professor, must be consulted on all script and script changes. The producer took a copy of the contract from the professor’s hand, turned a page or two and said: I have just consulted with you. At that point the producer turned and walked away.

Don’t we feel like the professor when the Team smiles, says everything is okeydokey and thanks us for being at the meeting? Yes we do.

Despite the mess, parents generally have a good intuitive notion about what is and what is not right with an IEP. Many parents, though, do not know effective ways to complain and prove their complaints.

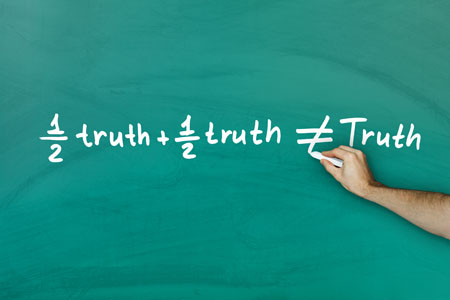

We must define what we mean by complain.

Informal complaint: A few Synonyms: squawk grumble, gripe, bellyache, protest, and beef.

Formal complaint: Charge, pleading, bill of particulars, allegation,

That means that when we want to complain (advocate for change) at a Team meeting we want the school district to do something or stop doing something connected to the IEP or 504 plan. And, it means we must complain in a way the procedures and the “system” can deal with our complaint. The procedures and the “system” cannot process our squawks, grumbles, gripes bellyaches, protests and beefs.

Does that mean we cannot squawk, grumble, gripe, bellyache, protest and bring up our beefs? No. We can, but we must not allow our anger to take over the conversation. Remember the one who can make you angry is the one who can control you.

Which brings us to the reason for this article: Getting heard.

In the legal sense, complaining and talking about complaining has been going on for centuries. During the 6th Egyptian dynasty[1], for example, Ptahotep issued an important instruction. It is paraphrased here.

The Instruction of Ptahhotep (pronounced Pta-hotep)

If you are one who leads,

Listen calmly to the speech of one who pleads;

Don’t stop the pleader from purging their body

Of that which they planned to tell.

One in distress wants to pour out their heart

More than that their case be won.

About one who stops the pleas

One says: “Why does one reject it?”

Not all one pleads for can be granted,

But a good hearing soothes the heart.

We want someone to listen.

Admission:

Yes, I am guilty. Sometimes I do get antsy when a frustrated parent calls and I’m eager to drill down to what the real issues are. And yes, parents do actively remind me of that when they call and I urge them to focus on the reason they are having trouble with the school district. I sometimes forget that they want – and need – to pour out their heart. When it happens I have a silent talk with myself about a universal truth of human nature:

We human beings will tolerate all kinds of abuse except one: We do not tolerate being taken for granted. Still, we cannot get far toward getting what a student needs without knowing what legitimate [2] complaints exist in a student’s Plan and the way the Plan is implemented. Why go through all of that? Because when we need to complain about something we believe is not right (legitimate) in an IEP or 504 plan, our complaints are always related to a legal question:

Does the Plan provide a free appropriate public education or not?

Has an action, lack of action, or policy caused discrimination or not?

The IEP is the school district’s legal definition of an individualized free appropriate public education for a specific student. The primary question all school district attorneys ask-

Is The IEP Legally Defensible?

We should also ask the same question: Does the IEP provide the student a free and appropriate public education at public expense? And if not, why not, and what do we want the school to do about it (what is the remedy)?

Why should we use this approach?

Is all of this nit-picky use of words and looking for the supporting facts necessary for making your argument (presentation) during a Team meeting? Yes. It is necessary because we are always more likely to get more cooperation from the school district if we can mutually fix the problem with the least amount of legal wrangling. Another reason is what happens or does not happen in a Team meeting may well be the factual foundation for an administrative or formal complaint later.

Find The Real Issues

Find The Real Issues

Whether we want to complain at a Team meeting or by a more formal way of complaining, the question is how do we decide what the real issues are? Yes, correctly identifying the real issues is a lot of work. We need to think like an investigator. We also need to think about what an IEP is. What is it supposed to do? What is its function?

We can begin by not thinking about an IEP as a series of pieces and parts. The IEP is a whole document. Unless we look at the whole document we, and the school district, sometimes name solutions before naming the unique educational needs of our student. As you know, this is a serious problem.

We can change that by asking a basic question.

The IEP and its function

The function of a Plan is to provide an educational benefit to the specific student named in the IEP.

An analogy:

Nobody wants a checking account at the bank. What we want is safe place to store our money so we can pay for things with a check instead of carrying around a bunch of cash. We want an ATM card or a credit card for the same reasons.

Likewise, nobody wants an IEP for the sake of having one. We want what an IEP will do; deliver; an education plan tailored to the student’s unique educational needs at no cost to the parent and helps the student make adequate annual educational progress no matter what the student’s disability is. Every student must receive an educational benefit.

The similarity of a bank checking account and an IEP is exactly the same: Both perform a function that delivers us a benefit.

The analogy of the checking account ends there because we cannot just close our IEP account with the school district and find another one in town to use.

Well, ok, you know the IEP is supposed to perform a function, which is to provide a free and appropriate public education. But woe is me: It is getting harder to get necessary changes made. I mean, it’s like pulling teeth. You’d think every school district member of the Team has a financial stake in a student’s IEP whether it is good, bad, or indifferent.

Thinking about the function of an IEP or 504 plan can change the conversation with the school district. An IEP is not a matter of “this piece” and “that piece.” All the “pieces: must be functioning in harmony to give a student what the student needs, get the protections of the rules, and offer educational benefits.

Form follows function

Form follows function is a principle associated with architecture and industrial design. The principle is the shape of a building or object should be based on its intended function or purpose.

And so it is with the “pieces” of an IEP. All the IEP or 504 plan[3] “pieces” must be designed such the finished product, the Plan, delivers what it is intended to deliver. That is why the present levels of academic achievement and functional performance (PLOPs) section is the first piece of the Plan. It is the cornerstone of the plan’s architecture. The information in the present levels must be objective and backed up with measurable information. “Nimrod is a pleasant boy and everyone loves him” is a purely subjective statement. The Plan cannot be appropriate for the student if the present levels are not objectively stated, have measurable information and is factually correct.

The theory of the IDEA

The theory is the evaluation is the foundation for an IEP. It is no mistake that an evaluation of a child suspected of needing special education is the top box the school has to check off before anything else happens to create an IEP. That evaluation is intended to prove that a child is or is not eligible for special education and, to define the unique educational needs of an eligible student.

You might say the evaluation is the foundation that supports an IEP because the architecture of a unique IEP must stand firmly attached to the evaluations. Educational Placement, then, is supposed to be decided by how the student’s unique educational needs must be met and where the specifics in the IEP should be delivered by the school district.

All IEPs are not created equal

Theory vs. The Real World In a nutshell

First Step: Evaluation

Evaluations are properly used for:

- Screening

- Eligibility

- defining unique educational needs

- determining present levels of educational performance

School districts currently use evaluations that concentrate on eligibility at the expense of evaluations for the other purposes. Schools have tried to use eligibility evaluations for just about everything.

Second Step: Two piles of needs

- conditions needed for learning, (often these conditions are defined in the evaluations, but never make it to the IEP) and

- conditions needed for educating. (for example., modifications, accommodations, specialized instruction).

Third Step: The IEP must fit the student.

The IEP should give us a clear picture of the student. All too often, though, we get a clear picture of this piece or that piece, but not of the student. Begin by assessing the student’s unique educational needs.

Highlight the child’s unique educational needs and the evaluators’ recommendations. Compare the unique needs and recommendations to the IEP. Drill down and find how many of those unique educational needs and recommendations are dealt with in the IEP.

One way of tracking the information is by using a spread sheet program such as Microsoft Excel or another similar program. Libre Office[4] has just such a program. It is free and works just as well as Microsoft Excel.

If the only issue in special education is whether an IEP provides FAPE, then the facts of a case will eventually become the “argument” that you will make during IEP meetings or in a complaint or a request for a formal hearing. If the underlying facts are defined poorly the arguments become poorly defined as well. Children identified as having disabilities under the IDEA are entitled to a Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE).

Definition of a Free appropriate public education. 20 USC 33 § 1401 (9) The term “free appropriate public education” means special education and related services that—

(A) have been provided at public expense, under public supervision and direction, and without charge;

(B) meet the standards of the State educational agency;

(C) include an appropriate preschool, elementary school, or secondary school education in the State involved; and

(D) are provided in conformity with the individualized education program required under section 1414 (d) of this title.

Identify each suspected violation separately.

Begin with the Present Levels of Academic Achievement. Then, move through the other sections of the IEP one section at a time. Do not skip any section. Remember the IEP is a whole document – not pieces parts.

For each suspected violation, identify the State special education regulation that applies to that specific suspected violation. For example, if you believe the school district’s notion of ESY for your child is a violation, go to your State’s regulations that control ESY. Do not overlook the State definition of ESY (or any other terms).

The next step is to compare the facts as you find them in the records to the exact language of the regulation.

Hypothetical Example

Nimrod’s mother wrote several letters to the school to ask the school to give Nimrod ESY during the school year and during the summer vacation.

At the last IEP meeting she asked for ESY again. The District’s response has been consistent: (a) Nimrod does not quality for ESY because Nimrod has not regressed and (b) even if Nimrod qualified for ESY, the District limits ESY services to the first three weeks of summer vacation. The school district has not given Nimrod’s mother an explanation (in a prior written notice) that explains why the district turned down her request and the district did not explain any alternatives the district considered.

For this illustration we will use the Ohio special education regulations. The title of the Ohio special education regulations is the Ohio Operating Standards for the Education of Children with Disabilities. NOTE: Be certain that you use the most current version of your state’s regulations.

Ohio defines ESY in the section under the Free Appropriate Public Education Rule 3301-51-02(G).

The legal question (issue) in this hypothetical is:

Under the Ohio Operating Standards (the Ohio regulations) Rule 3301-51-02(G), did the school district deny a free appropriate public education for Nimrod by denying him ESY services? Ohio defines ESY in the section under Free Appropriate Public Education Rule 3301-51-02(G).

Extended school year services

(1) General

(a) Each school district must ensure that extended school year services are available as necessary to provide FAPE, consistent with this rule.

(b) Extended school year services must be provided only if a child’s IEP team determines, on an individual basis, in accordance with rule 3301-51-07 of the Administrative Code, that the services are necessary for the provision of FAPE to the child. Additionally, the school district shall consider the following when determining if extended school year services should be provided:

(i) Whether extended school year services are necessary to prevent significant regression of skills or knowledge retained by the child so as to seriously impede the child’s progress toward the child’s educational goals; and

(ii) Whether extended school year services are necessary to avoid something more than adequately recoupable regression.

(c) In implementing the requirements of this rule, a school district shall not:

(i) Limit extended school year services to particular categories of disability; or

(ii) Unilaterally limit the type, amount, or duration of those services.

The definition of ESY in Ohio is at Rule 3301-51-02(G)(2).

Definition

As used in this rule, the term “extended school year services” means special education and related services that:

(a) Are provided to a child with a disability:

(i) Beyond the normal school year of the school district;

(ii) In accordance with the child’s IEP; and

(iii) At no cost to the parents of the child; and

(b) Meet the standards of the Ohio department of education.

How is the school year defined? Is it limited to a specific number of instructional days in a calendar year or does it also include the number of instruction hours per day for the school year? We know that extending the school year for ESY means services during the summer break. Can we also include additional instruction hours during the school year as ESY services?

Relevant Facts:

1. Nimrod is a 13 year old student enrolled in the Old Overshoe Middle School.

2. He has had an IEP since he entered the 4th grade.

3. His category of disability is Other Health Impairment (OHI) because the school nurse diagnosed Nimrod’s condition as opposition defiant disorder (OCD) when he was in the 4th grade.

4. A series of independent evaluations by licensed evaluators show Nimrod has a speech and language processing problem.

5. The present levels of academic achievement and functional performance section of his current IEP include the following statement: “Nimrod’s defiant behaviors interfere with his willingness[5] to learn to read and write at grade level. Nimrod’s mother refuses to allow medication. His willingness to learn is a function of his defiance and he could read and write at grade level if he was medicated and he chose to learn.”

6. Nimrod’s latest reading level as recorded by the school district in his current IEP shows that he is three years behind in reading and writing.

Take the facts and the language of the regulation for exactly what they say. Do not imagine other facts that might also be present.

Come to your conclusion and answer this question:

Under the Ohio Operating Standards (the Ohio regulations) Rule 3301-51-02(G), did the school district deny a free appropriate public education for Nimrod by denying him ESY services because it

(1) would not give him ESY services during the school year

And/or

(2) limits ESY services to the first three weeks of summer vacation.

Is it worth spending time to wring out your argument in this way for an IEP meeting? I leave that to you to decide. Just remember, though, the IDEA does not give local education agencies the privilege of having the “I said so” doctrine.

Use the “formula” we just used for getting ready to complain.

About complaints

We can make a complaints at Team meetings as well as in a State administrative complaint. We can also ask for a due process hearing. The difference is the forum and the degree of formality of the complaint and how the complaint is decided. Always try to resolve a complaint at the lowest level of formality needed.

The old saying about the squeaky wheel gets the grease is a true comment about the way we sometimes complain. However, squeaks are mostly just annoyances. The school district can easily discard or ignore constantly squeaking wheels. (Mom is overprotective, wants a Cadillac education, and on, and on, and on).

Nevertheless, well thought out complaints presented in a clear way are necessary. Public schools do not try hard to find dissatisfaction. And, they do not correct problems presented to them unless those problems come to their attention by strong advocacy.

Key Concept:

An Individualized Education Plan (IEP) is nothing more and nothing less than the education agency’s formal legal definition of FAPE for a specific student. Every underlying issue, or question, is about FAPE, and every public education agency has a statutory duty to provide FAPE for every eligible disabled or handicapped child in its jurisdiction.

Pick one:

ESY

Attorney Fees

Alternative Placement

Assistive Technology|

Assistive Services

Present Levels of Educational Performance

Annual Goals and Short Term Objectives

Transportation

Independent Evaluations

Discipline

Think of school district decisions like this: Every decision about special education is a final decision unless a challenge to that decision made. Even choosing to ignore a situation and do nothing is an administrative decision. Remember this the next time a special education administrator says, “My hands are tied.”

The formula, or recipe, for challenging decisions is in the procedural safeguards.

Identify the real issues by objectively analyzing the facts

If we have not been trained or taught how to objectively analyze the facts and issues in a special education conflict, we have a difficult time identifying the issues (questions) of their case. Here is a quick introduction to helping you decide the real issues of a special education case:

1. Go through the IEP section by section.

2. For each section that you suspect has a procedural violation that denies FAPE identify the state special education regulation that controls that particular procedure. Examples are Child Find, evaluations, present levels of academic achievement and functional performance, transition, etc. If you are not familiar with the IEP sections just use the state regulation table of contents to guide you through finding the right rule and section.

3. For each unique violation you believe happened, gather the documented evidence that you have that proves – or tends to prove – (a) the violation occurred and (b) the violation caused harm (denial of FAPE).

4. Analyze the suspected violation and denial of FAPE one at a time. Do not jump around. A good way to handle this is to use a separate file folder for each suspected violation.

First, write the rule[6] word for word on the first page of the analysis. Next, compare the facts that you have documented. List each fact separately. Just list them as #1, #2, etc.

You can identify them by the name of the document. Example, #1: Letter from Ms. Special Education Director, dated x-xx-xx

Next, compare the facts with the exact language in the rule. If the facts show that the regulation was violated, then you can argue that a denial of FAPE happened.

Example analysis outline:

1. Write your question:

Did the school district deny Nimrod a free appropriate public education because it failed to properly evaluate under the Child Find Provision (write the regulation number)

2. Write the exact language of the regulation on your analysis page.

3. Compare the facts with the exact language of regulation. The facts will show whether the district did or did not follow the Child Find provision.

4. Draw your conclusion. The school did (or did not) violate the Child Find regulation and as a result, denied Nimrod a free appropriate public education.

Note: With the exception of some procedural differences and the so called educational benefit standard,[7] the substance of a free appropriate public education in Section 504 and the IDEA are the same.[8] You can read a full explanation of FAPE under Section 504 at http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/edlite-FAPE504.html

“Wresting ambiguity from the jaws of clarity.”

That remark came from Judge Alex Kozinski as he delivered a paper on the language in contracts.[9] I think we can steal it fair and square by applying that concept to IEPs and special education meetings

IEP graffiti – Excerpts from real IEPs

The following is a collection of excerpts from IEP documents that Otis[10] gleaned from our files during 2000-2001. If you have some that you would care to add to this collection . . . feel free to do so. Just send them to askotis@shoreham.net

1. “[The Student] has a language-based Learning Disability which has made it difficult for him to access reading, spelling and writing instruction.”

Translation: This student has a learning disability which impedes his ability to use language. As a result of that disability, he is not able to demonstrate that he is getting an adequate educational benefit from his reading, spelling, and writing instructions.

2. “Reading comprehension is difficult for [the Student]. He has an easier time understanding narrative than non-fiction.’’

Comment: The fiction is that the writer of the sentence above is an educated educator.

3. “The Student] is a careful reader who takes him (sic) time with the decoding process.”

Translation: The student either has a neurological disorder or we have not taught him how to read. We will obscure all of this in the record by assigning a catch-all phrase such as “decoding process,” and use it to explain that he is a slow and careful reader.

And, more from the same IEP. .

“At times this effects (sic) his level of understanding because he forgets what he is reading about.”

Translation: “We’ve really, really tried, but it is all the Student’s fault because he is such a slow reader. He forgets from one word to the next what he is reading.”

“The [Student] needs to work on his automacticity with words to increase his rate of comprehension.

Question: Huh? Can anyone out there decode the word automacticity in this context?

Automaticity

1. the state or quality of being spontaneous, involuntary, or self-regulating.

2. the capacity of a cell to initiate an impulse without an external stimulus.

http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/automaticity

Also found in: Dictionary/thesaurus, Encyclopedia, Wikipedia.

automaticity /au·to·ma·ti·ci·ty/ (-mah-tis´ĭ-te)

4. The following sentence was the entire transition plan for a child in Florida:

“[The Student] will be exposed to a variety of prevocational activities to better determine his interests.”

Question: Care to try to translate that into a transition plan? Can’t you just imagine what might happen here if the school folks said to the kid, “Look, kid, we are going to ask you to go expose yourself in front of a variety of prevocational activities”?

5. From a Florida IEP:

“During bathrooming [the Student] will pull his pants down with verbal prompts as needed 80% of the time.”

Question: Has anyone seen my verbal prompts? Hurry, I gotta bathroom.

“After toothbrushing, [the Student] will use a damp washcloth to wipe his mouth with verbal prompts 80% of the time.

Comment: We are hopeful that the Student does not wipe his mouth with the same verbal prompts he used to pull his pants down (80% of the time) for bathrooming. Perhaps, the verbal prompts not used 20% of the time for pulling his pants down are left-overs, and can safely be used for wiping his mouth after toothbrushing.

“Toileting is a priority need for the parents and school.”

Comment: Now let’s just think about that for a moment. Yes, toileting is a priority for all human beings, including parents. But – can you just try to imagine a school with gastric distress?

And from a Statement of Present Levels of Performance description from the same Florida IEP:

“[The Student’s] emotional psychological and behavioral issues are integrated parts of his unique educational needs. It is critical that he generalize behaviors across all environments.”

Request: If any reader can translate the statement above into an education plan, please write to me. I would really, really, really, like to know what it means.

6. From a short term goal description from a Kentucky IEP:

“Play or attend to functional computer.”

Translation: “Here’s the deal, kid, ask the teacher which computer in the room is functional. You should then either play with it – or simply attend to it.”

Noteworthy: The Goal, for which the short term objective was written was absolutely blank: Nada. Zip. El Voido.

7. Another of our favorite short term objectives:

“New tasks will be introduced bi-weekly.”

No comment necessary.

8. Graduation: The following appears on a student’s IEP graduation options page (Florida).

Under Graduation options, a check mark appeared in the box for the option “Exceptional Student Certificate of Completion.”

In the next section, appearing on the same page, the following comment is made:

“[Student’s] intellectual functioning level does not permit him to understand the school rules as outlined in the “Student’s Rights and Responsibilities Handbook.”

Question: What, other than time served, did the student complete during 12 years of being in school? A “certificate of completion” is reminiscent of a lyric line in a song from a television western series of years gone by: “Move ‘em in, head ‘em out – Rawhide.”

9. One of our favorite recommendations comes from a letter written to a student’s parents in the state of Tennessee by a school counselor. As background information, you should know that the student was, and always had been, placed in a fully self-contained segregated classroom with disabled students, all of whom were classified as severely autistic or mentally handicapped, or both.

“It is also felt by the undersigned that [the Student] benefits a great deal from the classroom group sessions where he has an opportunity to see and learn from his peers participation in affective settings.”

Right. . .

10. This is one of my favorite annual goals. It appeared in an IEP from New Hampshire.

“[The Student] will demonstrate body part identification with verbal prompts only.”

Question: How does one do that? Maybe, in the same way, one could pull down one’s pants with verbal prompts. “Now let me see, where did I put those verbal prompts?” “Maybe they are in my locker, no – in my backpack – no -.” “Teacher, I can’t demonstrate a body part because I can’t find my verbal prompts.”

11. “Parent was not present at the actual 6/12/01 meeting.”

Question: Is this some indication of a meeting shell game? Which pea is the meeting under? “Oh – sorry mom, you missed it again – we had a virtual meeting on 6/12/01, but you missed the actual 6/12/01 meeting.”

12. “With some verbal input from [Mom], she requested that the team draft an IEP for her.”

Question: Would anyone out there care to outline this sentence? Now let’s see: subject, predicate, object of whatever it is. Oh, I see. This is an outcome-based sentence.

We hope some of these suggestions and methods help you avoid dark and stormy nights. Remember that you know your child better than anyone else. Making the Team meeting your forum for arguing from a legal perspective instead of on intuition will make your advocacy stronger.

Thanks.

—Brice

You are invited to post a question for Brice about this article or any other special education question on the INCIID Ask The Advocate Forum by going to

[1] 2300-2100 B.C.

[2] The word legitimate comes to us from the mid-15th century by way of the middle French word ligitimer, which comes from the Latin word legitimus (lawful) which comes from the Latin word Legis (law). Today we also use the informal synonyms “genuine” and “real” in the sense of a “genuine complaint” or the “real issues”.

[3] Under the amendments to Section 504 through the amendments to the ADA, Section 504 now includes a free appropriate public education which with a few exceptions, mirrors the FAPE requirement in the IDEA.

[4] http://www.libreoffice.org/

[5] Notice here that the district shifted the cause of Nimrod’s problems to his “willingness” to learn to read and write at grade level.

[6] A rule is a regulation or statute.

[7] The standard under Hendrick Hudson Dist. Bd. Of Ed. V Rowley, 458 U.S. 176 (1982) is “a basic floor of opportunity. However, that is no longer the standard in some Circuits. Special education attorney Dorene Philpot has y argued this issue and she has outlined the case law on this subject. You might find that discussion and outline on her website. http://www.dphilpotlaw.com/html/special-ed.html If it is not on her website just drop me an email to brice@shoreham.net and I’ll send it to you. Put Philpot in the subject line.

Under Section 504, “T o be appropriate, education programs for students with disabilities must be designed to meet their individual needs to the same extent that the needs of nondisabled students are met.”

[8] “No otherwise qualified individual with a disability in the United States . . . shall, solely by reason of her or his disability, be excluded from the participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” (Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, as amended, 29 U.S.C. 794. )

[9] Judge Alex Kozinski, Distinguished Jurist In Residence Program, Touro College Jacob D. Fuchsberg Law Center, March 16, 1994.

[10] Otis the wonder dog oversaw the office from 1994 until he went to his beloved meadow behind the office for the last time in 2007.